St Florian’s Gate

St. Florian’s Gate served as the main entrance to the former Kraków. It allowed entry to the city and was a military building. Currently, it is one of the most famous monuments in Kraków. It was built as a defensive tower. Its 34-meter silhouette rises picturesquely between the Barbican and the beginning of Floriańska Street. The first mention of it comes from 1307. It was expanded and increased in height until the 16th century. Until the 19th century, the role and layout of the inner area and some external parts were changed. The building was erected on a rectangular plan with dimensions of eight and a half meters and just over nine meters. Its walls are made of irregular, light-colored stones. Only the upper section is made of brick. A narrow strip of bricks also appears in the central part of the wall facing Floriańska Street. The building is covered with a brick hip tile roof. It is crowned with a steeple covered with a now green, copper sheet metal helmet and a gold-plated flag.

The gate opening is about three and a half meters high, almost four meters wide, and is topped with a sharp arc. In the wall on the west side, there is a small chapel. When entering from the side of the Barbican, you can see it on your right. Above the altar, there is a copy of the icon of Our Lady of Piasek.

Above the gate opening on the wall facing Floriańska Street, there is a porch. It is surrounded by a decorative stone balustrade made of gray sandstone. From the porch, you can enter the Chapel of the Virgin Mary.

In the recess situated a few meters higher, there is a bas-relief of Saint Florian. He is depicted as a Roman soldier in gilded armor. He is holding a red banner in his left hand and a bucket in the right one. As the patron of firefighters, the saint is pouring water from the bucket onto a building which is much smaller than him.

The northern wall facing the Barbican is decorated with a bas-relief depicting an eagle. It is situated at a height of almost twelve meters. The crowned eagle with outstretched wings is depicted on the background of a shield. The highest, brick part of the tower walls is surrounded by a protruding porch. It is supported by light-colored stone brackets. The porch is fully enclosed. Its walls have some small arrowslits. This is the so-called machicolation.

St. Florian’s Gate was to be demolished for the third time at the beginning of the 20th century when a tram line was being built at the site. The problem was that the height of the passage under the gate did not fit the pantograph, i.e. an apparatus mounted on the roof of a tram to collect power. Fortunately, a decision was made to widen and deepen the passage. As a result, the monument survived. However, for the next dozen years or so, drivers operating the narrow-gauge trams had to fold the pantograph every time they would go under St. Florian’s Gate.

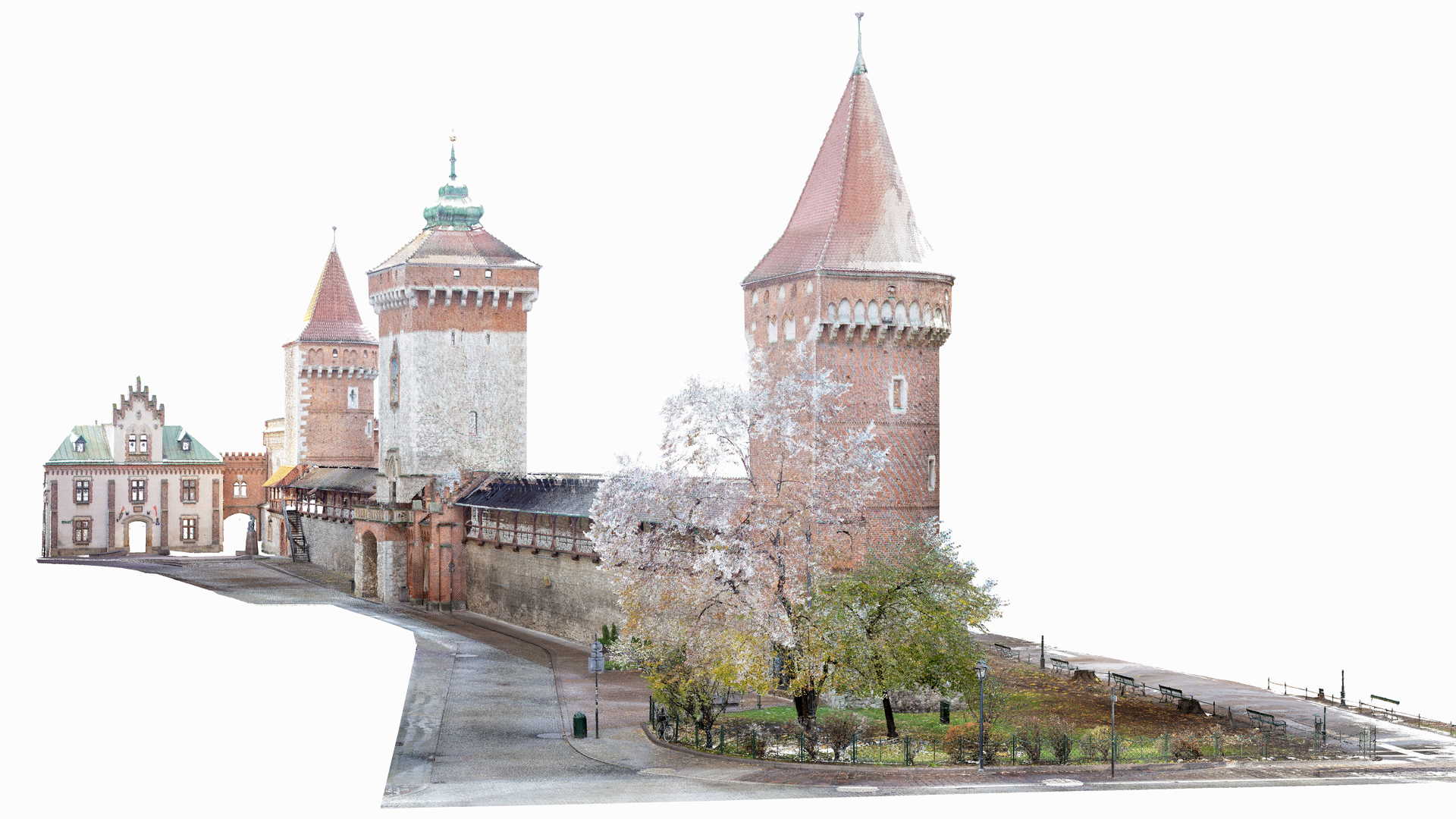

The Pasamoników Tower

The Pasamoników (Haberdashers’) Tower is one of the elements of Krakow’s medieval walls and defensive structures. It is situated at the beginning of Pijarów Street, at the intersection with Szpitalna Street. Its origins date back to the first half of the 14th century. It was expanded in the second half of the 15th century. The name comes from a guild of craftsmen – haberdashers, who made ornaments for garments. The guild was obliged to defend the tower in the event of a siege. The building represents the Gothic style. It is 31 meters high. Its oldest part – the base – was built on a square plan with a side length of seven and a half meters. Irregular, light-colored stones were used for construction to form a six-meter high tower. At the top, there is a semicircular brick section which was added later. Most of the bricks are red, but some are dark gray. The straight wall faces Pijarów Street. The semicircular part – the Planty Park. The tower is topped with a steep, pointed roof made of brick tiles and crowned with a slender turret with a metal flag.

The entrance to the tower is situated in the wall facing Pijarów Street. This is where the line between the stone and the brick is irregular. A four-and-a-half-meter high gate, which leads into the tower, is finished with a semicircular arch.

It is closed by an iron grille. At a height of thirteen meters, you can see a rectangular stone window. Almost two meters above it, there are two decorative, shallow recesses. They look like bricked up windows topped with arches. At the top, just below the roof line, there are two arrowslits and three semicircular recesses situated alternately.

The beginning of the tower’s semicircular section from the eastern side, i.e. facing Szpitalna Street, is supported by a stone buttress. It is as high as the stone base – six meters. In the brick wall of the upper edge of the buttress, there is a small door.

The semicircular part of the tower has four arrowslits. The top section of the tower is surrounded by the part protruding beyond the main wall, i.e. the so-called machicolation. It is supported by twenty-nine stone supports. At the bottom of the machicolation wall, there is a strip of decorative, semicircular recesses. At the top, near the edge of the roof, there are seven arrowslits. The gray bricks on the walls of the tower were built in so that they form a pattern of diagonal lines.

St Florian’s Gate – north elevation

St Florian’s Gate – south elevation

Chapel of the Blessed Virgin Mary in St. Florian’s Gate in Kraków

The Chapel of the Blessed Virgin Mary is situated on the ground floor of St. Florian’s Gate. It was built during the renovation of the monument carried out in 1885-1886. The works were commissioned by Prince Władysław Czartoryski who wanted a chapel for his family. The interior was designed in the neo-Gothic style by an architect from Kraków, Wandalin Beringer. The style mimics the features of the Gothic style, such as sharp arches. The chapel was constructed inside the gate built on a rectangular plan, it is eight and a half meters long, nine meters wide, and almost twelve meters high. You can enter the chapel from the porch. In front of the entrance, there is a stone altar with a cross and a figure of Christ on top of it. Behind the altar, you will find a small stained glass window depicting the Virgin Mary. The chapel was painted with vivid colors. The walls are red and yellow, and the vault is blue.

Following the example of Gothic art, the chapel has a rib vault. The skeleton of the vault is made of thick arches which look like ribs. In the Czartoryski chapel, they are painted red and gold. They converge at the central, highest point of the vault, where the Pogoń coat of arms is located. It displays a knight on horseback, raising a sword. The line where the walls and the vault meet is semicircular.

It is marked with a painted yellow stripe decorated with a pattern of leaves. At the top, the walls are red and in the bottom half – yellow. Decorative yellow stripes in the shape of arcs are painted on the border of these colors. They feature patterns of blue and red leaves. On the yellow section of the wall, the pattern is formed by rows of blue squares, diagonal lines, and circles.

The cross on the altar is made of wood. The cross itself is dark brown and the body of Christ is light brown. The sides of the stone altar are painted white, with vertical navy blue lines. The columns on both sides are navy blue as well. The altar stands on a low platform. The floor of the chapel is covered with ceramic tiles in the shape of regularly arranged beige and navy blue rhombuses.

The entrance to the chapel has the form of a portal, i.e. a decorative stone opening. It has the shape of a pointed arch. The chapel is at the site of a former ‘harrow chamber’. It was a room with a device for lowering the portcullis. Its grille was also called a harrow, hence the name of the room.

Defensive walls

The preserved fragment of the defensive walls of Kraków is situated between the Pasamoników (Haberdashers’) Tower, St. Florian’s Gate, and the Carpenters’ Tower. It is almost a hundred meters long. The walls come from the turn of the 13th and 14th centuries. Their highest part was added in the early 20th century. The walls reach a height of about 10 meters and are almost two and a half meters thick. They were mainly built of the so-called crushed stone. The pieces of light-colored stones are irregular. The highest section of the wall is made of bricks and covered with a roof, which also covers a wooden porch on the south side of the walls facing Pijarów Street.

The upper edge of the stone section of the walls is shaped like rectangular teeth, which is called a battlement. The ‘teeth’ occur at intervals and the gaps between them are now filled with bricks. Every other stone ‘tooth’ has a narrow rectangular embrasure.

In addition, there are 17 arrowslits with a narrow, vertical opening in the walls, together with several arrowslits in the shape of a keyhole (the slot ends with a circular hole). The stone section of the walls reaches a height of about eight meters. The porch that runs along the walls is one and a half meters wide. It is secured by a wooden and metal railing. At the top, there are crossbeams supporting the canopy.

On the walls facing Pijarów Street, there are plenty of colorful paintings. It is a special open-air gallery. The canvases show a wide variety of topics: landscapes, portraits, monuments of Kraków, and images of animals. Many of them are copies of works by famous painters.

History of Kraków’s defensive walls

The beginnings of fortification systems

The history of defensive structures, or fortifications, is as old as the history of human settlement, of the formation of the first big city and state centers in the world, and its origins are associated with the need to protect such centers. The term “fortification”, or “fortify” itself (as an action), comes from the Latin fortificatio and was created by combining two Latin words: fortis – ‘strong’ and facio – ‘to make’. Its general meaning, therefore, refers to strengthening, making a given area stronger and more secure. The term “fortification” also includes a structure or a facility that provides additional protection to a specific territory. Fortifications can be broadly divided into two categories: 1. field fortifications that are built on an ad hoc basis, to meet a sudden need, and 2. permanent fortifications used to protect a given area in the long term.

The history of permanent fortifications goes back to the 3rd millennium BC and is associated with the emergence of great ancient civilizations that developed in the Nile, Tigris and Euphrates, Ganges and Yangtze river valleys. The flagship example of a fortification, whose construction began around the 3rd millennium BC, is the Great Wall of China, which was constantly expanded over the centuries, ending up as a huge, monumental structure. Other great fortifications of ancient times include the Egyptian fortresses of Abydos or Semna.

he most famous Polish settlement with a well-developed defensive system is Biskupin, situated in the Pomerania region. It existed in the period of the tribal communities, i.e. around 700-400 BC. Its fortifications consisted of a wooden and earth embankment reinforced with a palisade and a fortified wooden entrance gate, which was accessed by a footbridge over the lake surrounding the settlement.

However, thanks to the extensive archaeological research related to the construction of the expressway network in Poland, multiple remains of defensive settlements much older than the aforementioned Biskupin have been discovered in the past few years. Currently, the settlement discovered in the village of Sadowie in the Kocmyrzów-Luborzyca commune, situated several dozen kilometers from Kraków, is considered the oldest one. It dates back to the Bronze Age: 2200-2050 BC. The settlement covered a large area, equivalent to five football pitches, and was located on a hill. It had an earth embankment reinforced with stones and a moat 2 meters deep.

The beginnings of fortifications in Kraków

Kraków has a perfect area with natural fortification properties in the form of Wawel Hill, which shows traces of human presence dating back to the Stone Age and representing the so-called Prądnik culture (70,000-48,000 BC). The hill was a convenient settlement area for millennia, it was where traces of the first Slavs appeared in the 6th century AD. The oldest relics of Wawel’s defensive structures, on the other hand, come from the 9th century. Those fortifications surrounding the entire hill are most likely associated with the state of Vistulans and with a possible residence on the hill owned by the “pagan prince sitting on the Vistula” mentioned in the life of St. Methodius. They took the form of an earth embankment. In the following centuries, the fortifications were expanded by adding wooden elements, including a palisade.

Wawel Hill becoming a ducal center provided an impulse for people to settle at its feet. The earliest settlements were established in the vicinity of Kanonicza and Grodzka streets, creating a gord, which in the 9th century was surrounded by an earth embankment.

It was also called Okół from the embankment forming a ring around the settlement. On the other hand, the areas of the present Old Town were then occupied by rural settlements of an agricultural and handicraft nature, without a defensive system of fortifications. This had its consequences in 1241, when the area of Kraków was invaded by the Tatar army, who completely burned down all of the buildings. It was one of the most significant events in the history of Kraków – the destroyed buildings left a huge empty space, which made it possible to introduce a new location act for Kraków under Magdeburg Law 16 years later. The location resulted in a number of processes that led to the creation of the city in its strict sense – creating a network of streets and plots of land for residential development, the organization of space for a large market square in the heart of the town – the current Main Square, and, most of all, creating the local government – municipal authorities. The highest authority in the city was then exercised by the wójt who had his seat in the so-called Gródek (hence the name of the contemporary street “Na Gródku” in the eastern part of the city). The area most likely had some features of a fortified area. It might have also had a brick defensive tower.

Kraków’s fortification system

The foundation of Kraków under German town law, i.e. the creation of an urban center, did include plans for surrounding Kraków with defensive structures. It was after another Tatar invasion in 1259 that it received serious consideration, however, the unstable situation in the fragmented country delayed the investment. It was Duke Leszek II the Black who, while in conflict with the magnates of Małopolska and Duke Konrad II of Masovia, had the support of the townspeople of Kraków and managed to provide the town with protection. In gratitude to the residents of Kraków, he issued a 1285 privilege allowing the construction of a wood and earth embankment surrounding the town. Although the works on such a large project were a burden to the municipal treasury, Kraków, which was experiencing rapid economic development at that time, was quick to build its first fortifications ensuring the safety of its residents. They did not have to wait long to test out the fortifications – at the turn of 1287 and 1288, Kraków was attacked by Tatars once again. This time, the town was successful in repelling the attack.

Although resistant to ranged weapons, wooden and earth fortifications were exposed to adverse weather conditions. Already at the turn of the 13th and 14th centuries, those fortifications started to be replaced with much more durable and safer brick fortifications. In Kraków, such a process dates back to the reign of Wenceslaus II (1291-1305). At that time, fortifications were built using stone bound with lime mortar. The height of the wall was even 10 meters, while its width was about 2.4 meters. On the top, there was a battlement on the outside (a crenellated wall about 0.5 meters wide), while on the inside, there was a footpath forming the so-called guard porch. From the porch, the defenders of the walls could directly hit the enemy with ranged weapons, aiming from the crenels. Sometimes, the walls had hoardings and machicolation boxes. Hoardings consisted of wooden porches hanging at the top front of the wall. They had holes in the floor so that it was possible to strike the enemy at the very base of the wall. It was also a good spot to pour hot water or tar over the enemies. Over time, wooden structures extending beyond the wall were replaced with brick ones, called machicolations; they were mounted on stone supports called corbels and protected the defenders much better.

Over time, wooden structures extending beyond the wall were replaced with brick ones, called machicolations; they were mounted on stone supports called corbels and protected the defenders much better.

The earliest historical sources in Kraków testify to the section of the city walls surrounding a hospital – next to the St. Cross Church (1301), the wall at today’s Anna Street (1310), fortifications at the Szewska Gate (1318), next to the Dominican church (1326) or at the former Garncarska Street – currently Gołębia Street (1343), and next to St. Stephen’s Church (1343). 1346, on the other hand, witnessed an important event – Krakow’s defensive walls were connected to those that had previously surrounded Okół. This way, the fortifications of Wawel, Okół, and the city itself were merged into one tight ring of fortifications.

The walls had multiple gates which were also an important defensive element of the city. Back in the period of timber and earth fortifications, there were only 4 gates – Floriańska (St. Florian’s), Sławkowska, Szewska, and Wiślna. After the modernization and construction of a brick system of fortifications, they had several floors, and their towers were topped with battlements. The gates were named after the streets they led to. In the 14th century, there were as many as 8 gates leading to Kraków. On the north side, there was the only gate that has survived until now – St. Florian’s Gate (the first recorded reference comes from 1307) and the Sławkowska Gate (1311). From the east, you could enter the town through the previously mentioned Butcher’s Gate (1289), which was later replaced by the Mikołajska Gate (1312) and the New Gate (1395) built in the 2nd half of the 14th century. In the southern part of the city – at the foot of Wawel, there was the Grodzka Gate (1298) and the Side Gate (1390). From the west side, there was the Szewska Gate (1313) and the Wiślna Gate (1310). Each gate was equipped with heavy, double gates and one or two portcullises, formerly called brony (“harrows”) – they were made of a combination of metal and oak wood. The entrance to the city was closed at night, even during peacetime. In addition, each gate had a lowered bridge crossing a dry or water-filled earth ditch, called a moat.

Moat

The moat, which additionally raised the defensive value of the entire fortification system, was dug along the entire route of the city walls, except for sections with natural water reservoirs. Kraków had such wetlands near Okół, from the south-west side – around the Na Groblach area. Moats were usually supplied with water from the surrounding rivers – in Kraków, it came from the Rudawa River, whose course in the Middle Ages was different to its current one.

At the end of the 13th century, people started the works to regulate the streambed of one of its branches – Młynówka, named after the numerous mills it powered. It was directed towards the city so as to connect the water, wetlands, and swamps surrounding Kraków into a single string. For this purpose, in the distant Mydlniki, a low head dam was constructed that altered the flow of the Rudawa River. The moat was effectively supplied with its waters in 1327.

Bay windows – the beginnings of fortified towers

Another stage of the expansion of the Kraków fortification complex took place in the 14th century when the four-sided bay windows protruding in front of the fortifications were built into the walls at regular intervals. The bay windows, initially corresponding to the height of the wall at which they were situated, served as the base for the later Kraków towers. They significantly increased the defensive quality of the walls, allowing guards to open fire from the side from embrasures situated at the top. Later, they became the basis of the following fortified towers: Barber Surgeons’, Bellows Makers’, Tinsmiths’, Gunsmiths’, Ceklarzy, Blacksmiths’, Saddlers’, and the Executioners’. Such conclusions seem correct because of their rectangular shapes in the lowest stories.

The process of building the bay windows and then converting them into fortified towers was extremely costly and time-consuming. Until 1473, 17 towers were built in Kraków, in the 2nd half of the 16th century – there were 33 towers, and by 1648 – 47.

As mentioned earlier, it was already in the Middle Ages that the towers were built from reconstructed bay windows and in places where the walls were broken. The fortified towers had numerous arrowslits extending towards the interior on several levels, which provided a convenient spot for shooting the enemy from vertical, horizontal and side positions. In Kraków, the staffing of individual defensive towers and sections of walls adjacent to them was the responsibility of individual craft guilds operating in the city. They also carried out the necessary repairs and renovations of the buildings. This was all confirmed through the royal decision of 1358, which was then repeated in 1475. Hence, the towers which are the preserved elements of the fortifications bear the names of professions, for example, the Carpenters’ Tower or the Joiners’ Tower.

Craft guilds

raft guilds were organizations gathering all craftsmen of a given trade in the city, e.g. shoemakers, blacksmiths, furriers, etc. They controlled the quality of products and their prices. They were the basic organizational unit of urban society during the Old Polish period. The guilds were headed by masters who had appropriate knowledge and experience in a given profession. They had to go through the entire process of vocational education from an early age, acquiring basic knowledge as apprentices, then performing slightly more complicated tasks as journeymen, in order to finally take the master exam, where they had to produce a perfect object. If their skills allowed and they correctly produced the ordered article – the so-called masterpiece, they became master tradesmen.

Each guild had a council of elders composed of the most experienced foremen to judge and settle all disputes and controversies within the organization. The rules and standards for the quality of the manufactured products were defined by the so-called guild statutes which were approved by the king for each organization separately. The statutes also regulated the rules and norms of behavior in social life as well as social and living issues for representatives of craft corporations. In addition, the guilds had their own funds, which were spent on weapons to defend the fortified towers and walls, because the guilds were obliged to assemble the armory stored on the defensive walls.

Bractwo Kurkowe (Brotherhood of the Rooster)

Since it was mainly the craftsmen’s duty to defend Kraków – representatives of municipal professional corporations who did not have knowledge and skills in the use of ranged or cold weapons, the city needed an additional organization with military training. This was the Kraków Brotherhood of the Rooster. Its name comes from the form of activity – shooting from a crossbow or a bow to a target put on a tall pole – a wooden image of a bird, i.e. a rooster.

The origins of the organization are unknown. They might have been associated with the construction of brick fortifications around the city. Written sources do not mention the Brotherhood of the Rooster until the 15th century. The activities of the city dwellers involved mainly shooting with a crossbow or a bow, later – with firearms and black powder.

What is more, every year there was a competition for the best shooter in the city, who would receive the title of the Rooster King. One historical source, the chronicle of Jan Długosz, describes a city fire in June 1455, which spread quickly because “the inhabitants of Kraków went outside the city to shoot to a bird”. The seat of the Brotherhood of the Rooster was situated outside the city walls, in the area of the Mikołajska Gate – where the shooting range and training area were. The Brotherhood of the Rooster trained the inhabitants of Kraków in the art of war basically throughout the entire Old Polish period, with the exception of the times of wars, sieges, and the occupation of Kraków. After the Third Partition of Poland, the organization suspended its activity, but in the 1830s it was reactivated as the Kraków Shooting Society with its seat in the Strzelecki Garden, in a new building constructed especially for the Society, called Celestat (‘shooting range’ in German).

Organization and operation of the defensive system

n the Old Polish period, there were so many craft guilds in Kraków that it was possible to entrust each of these organizations with a different fortified tower. During the periods of peace, the guilds also looked after the gates, and during a siege they manned them with their craftsmen. The furriers’ guild was responsible for St. Florian’s Gate, the Sławkowska Gate was looked after by tailors, the Butchers’ Gate (later Mikołajska Gate) – by the butchers’ guild, the Nowa Gate – by bakers, the Grodzka Gate – by goldsmiths, the Szewska Gate – by shoemakers, and the Wiślna Gate – by locksmiths. As for the guilds taking care of the fortified towers after the completion of the construction process in 1648, we know of the following fortified towers from the north of the city:

– two Innkeepers’ towers, the Haberdashers’ Tower, the Carpenters’ Tower, and the Woodworkers’ Tower (those three exist to this day), the Swordsmen’s Tower, two Shoemakers’ towers, and the Executioner’s Tower

From the west side, there were 17 fortified towers:

– the Ceklarze1 Tower, the Łaziebniki2 Tower, the Bookbinders’ Tower, the Belt Makers’ Tower, the Potters’ Tower, the Red Tanners’ Tower, the Cutlers’ Tower, the Tinsmiths’ Tower, the Leatherworkers’ Tower, the Bellows Makers’ Tower, the Barber Surgeons’ Tower, the Salters’ Tower, the Painters’ Tower, the Needle Makers’ Tower, the Gunpowder Tower I, the Saddlers’ Tower and the Masons’ Tower.

From the south, Kraków was protected by Wawel which had a separate system of fortifications and towers. On the eastern side, however, there were:

– the Goldsmiths’ Tower, the Coopers’ Tower, the Ringers’ Tower, the Saddlers’ Tower, the Blacksmiths’ Tower, the Gunpowder Tower II, the Black Tanners’ Tower, the Hatmakers’ Tower, the Clothmakers’ Tower, the Merchants’ Tower, the Comb Makers’ Tower, and the Gunpowder Tower III.

1 Ceklarze – the city mayor’s private security who were also responsible for keeping order on the streets.

2 Łaziebniki – workers employed in a public bath responsible for preparing baths.

St Florian’s Gate

St. Florian’s Gate played a special role in the entire fortification system of Kraków. It guarded the passage to one of the largest streets in the city – Floriańska Street, which led directly to the Main Square. It was also part of the route leading south through the Main Square and Grodzka Street to Wawel and the Royal Castle. Hence, it was called the Royal Route – Via Regia. It was this route that was used by Polish kings to enter Wawel Hill, where they always got a tumultuous welcome. Since St. Florian’s Gate guarded the most important entrance to the city, it also had appropriate additional fortifications. At the end of the 15th century, when the city was threatened by the raids of Turks and Tatars, King John I Albert decided to build one more element of the city’s fortifications in the fore field of St. Florian’s Gate – the Barbican, which was erected in 1498-1499. At that time, it was a completely innovative defensive element of the city and an extremely strong point fortifying the entire system. The wide moat, a series of drawbridges, and portcullises made it practically impossible to force it during an attack. What is more, the Barbican was connected with St. Florian’s Gate by the so-called ‘neck’ which was a narrow passage enclosed with walls on the sides and with a portcullis and gates.

Kraków’s fortification system served its role very well. In December 1287, the archaic timber and earth fortifications still managed to stop the Tatar invasion. In the 14th century, the defensive walls of Kraków were put to the test during an eight-day siege of the city by the troops of John of Bohemia during the Polish-Bohemian War in 1345. In the 16th century, on the other hand, Kraków faced a much more dangerous siege, led by Maximilian III, Archduke of Austria, who made claims to the Polish crown during the interregnum period. With the intention of conquering Kraków and crowning himself as the King of Poland in Wawel Cathedral, Maximilian approached the city on October 16, 1587, with an army of about 6,000. However, even a trick, which involved the German inhabitants of Garbar infiltrating the fortifications and opening the Szewska Gate for Maximilian’s troops, did not help the attackers. On November 24, 1587, this section of Krakow’s city walls was stormed, but managed to resist thanks to the tactical skills of Hetman Jan Zamoyski. The invaders also failed to attack the fortifications of Kraków from the side of the Franciscan Monastery.

17th century – Swedish Deluge

The city had to withstand an incomparably greater siege in the 17th century during the Second Northern War, in Poland referred to as the “Swedish Deluge”, which resulted from the Swedes’ desire to dominate the Baltic Sea and the claims of Polish monarchs from the House of Vasa to the Swedish throne. The Scandinavian troops reached Polish Pomerania on July 19, 1655, and with no resistance from Poles, they advanced quickly into the country. Upon the news of the invasion, Kraków decided to strengthen its fortification system to better prepare the city for defense during the siege. It was already at the beginning of August 1655 that the renovation of the city walls began and another defense line in the form of earth embankments was created in front of the proper fortifications. They stretched from St. Florian’s Gate to the Mikołajska Gate, while further in the south, sconces with palisades were placed up to the Grodzka Gate. Access to some of the city gates was blocked with boulders and earth.

In addition, the Rudawa River was regulated to supply and increase the water level in the moat surrounding the city. With an army of 16,000 Swedish soldiers, King Charles X Gustav approached Kraków on September 26 and launched an attack on Kazimierz, which was quickly captured. Swedish troops stormed Kraków from this side, attacking the Grodzka Gate, but the attack was repelled by the city infantry under the command of Mayor Andrzej Cieniowicz. The attacks of the Swedish troops on other sections of Krakow’s fortifications were successfully repelled as well. The defensive walls, fortified towers and gates of Kraków themselves passed the test during the entire siege. The city was not captured in combat, but the unfavorable situation in the entire country and problems with stocks in the city forced the defenders to surrender. It was not until August 1657 that Kraków was regained.

18th century – The last days of independence

The next big battles for Kraków and its siege took place in the 18th century, in the last years of the independence of the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth. After signing the “Treaty of Perpetual Friendship” with Russia on February 24, 1768, when the protectorate of Russia over Poland became official, a group of magnates decided to form a confederation against Russia. It took place in Bar in Podolia, hence the name – the Bar Confederation. The Kraków voivodeship was also the site of formal protests of citizens against the undermined independence – the signing of the confederation act took place in Kleparz on June 20, 1768. Wishing to deal with the disobedient voivodeship as soon as possible, Russia sent its troops to Kraków. On June 22, the city was attacked by a unit of Russian troops under the command of Lieutenant Colonel Bock. The attack is associated with a legend about the inhabitants of Kraków, who resisted the attack, defending the city walls. Since the attack of the Russians was carried out from the north, the defenders from the section between St. Florian’s Gate and the Haberdashers’ Tower got involved in the fights – representatives of the haberdashers’ guild (craftsmen who manufactured leather belts and fabric fringes). One of the haberdashers, Marcin Oracewicz, a Kraków burgher and a member of the Brotherhood of the Rooster, was a skilled shooter. He decided to target Lieutenant Colonel Bock who was in charge of the storming Russian troops. Since he had run out of ammunition, he loaded his musket with a button from his żupan. He managed to hit the commander and stop the attack on the city. A commemorative plaque attached to the walls of the Barbican reminds us of the legend. Although the first attack was repelled, Russian forces were growing in numbers, and on July 27 they surrounded the entire city. The numerous attacks of Moskals – especially at the Sławkowska and Mikołajska gates, where the defenders ran out of supplies, broke their fighting spirit. Soon the city was captured.

The war turmoil of the last decades of the 18th century was a time when Kraków was conquered by various troops – Russian, Polish, Prussian, and Austrian. Its fate depended on the international policy of the neighboring powers. In the end, in January 1796 (three months after the Third Partition of Poland), it fell into the hands of the Austrians. Kraków lost its strategic position when the borders were shifted and the city became part of a new administrative region – West Galicia, but also because at the time (the end of the 19th century), the city’s fortification system was already very archaic and could not fulfill its defensive role in the light of the developing martial art, including siege techniques. Therefore, under the decree of the Austrian emperor, the demolition of Krakow’s city walls began in 1806 – the moat was filled with earth and the destroyed fortifications served as a source of building materials. In 1810-1813, the demolition of walls accelerated significantly. The activities had the support of the city authorities as well – there was a popular argument that it would improve the hygienic situation in the city and make the city space more open. There is no doubt that the entire fortification system would have been demolished if not for the efforts of the senator of the Free City of Kraków, Feliks Radwański, whose efforts led to the most representative fragment of the walls being preserved with the towers of Carpenters’, Joiners’, and Haberdashers’, together with St. Florian’s Gate. The Barbican, which is currently the only original architectural monument of this type in this part of Europe, was also saved. Apart from the above-mentioned elements of Kraków’s fortifications, one of the oldest city gates has survived to our times as well, or, to be more precise, its shape, which can be clearly seen in the buildings of the Dominican Sisters’ convent, right at the end of Mikołajska Street where it reaches the Planty Park.

19th century – Kraków fortifications as a historical monument

In the 19th century, some modifications were made to the existing fragments of city walls – a small brick wall was added to put a roof over the guard porch, which had been missing before. In the 1890s, by the decision of Prince Władysław Czartoryski and according to the design of Wandalin Berninger. the room above St. Florian’s Gate inside the tower gained a neo-Gothic chapel of the Blessed Virgin Mary. The chapel was equipped with a stone altar with a large cross, which was originally located on the façade of the historic house “Under the Cross”.

The interior of the chapel, decorated with a polychrome with geometric and floral motifs, has a ribbed vault. The colors used in the interior refer to the colors of the Czartoryski coat of arms – Pogoń: yellow-brownish, red, and blue with gilded trimmings.

The city walls in their current shape are now part of the Celestat branch of the Kraków Museum, with a tourist route passing through it.

Video: