Haczów – Church of the Assumption of the Blessed Virgin Mary and St. Michael the Archangel.

Fun fact: carved hooks.

Under the eaves of the Haczów church’s chancel, we can see hooks (elements supporting the structure). Four of them, located on the southern wall, have unusual carved anthropomorphic shapes resembling geometrised masks. The meaning behind the masks is unknown, nor is it known why such ornaments were made on only four hooks.

Was the carved decoration of the chancel of the Haczów church abandoned before it was finished for financial reasons, or was it a case of the craftsmen becoming bored? Or perhaps these strange masks, looking like pagan deities, were to refer to the cultic and symbolic meanings of the number four (corners of the world, elements, temperaments)? It is difficult to resolve this issue now, but it is certainly a very interesting decorative element that is unique in Central Europe.

Murals:

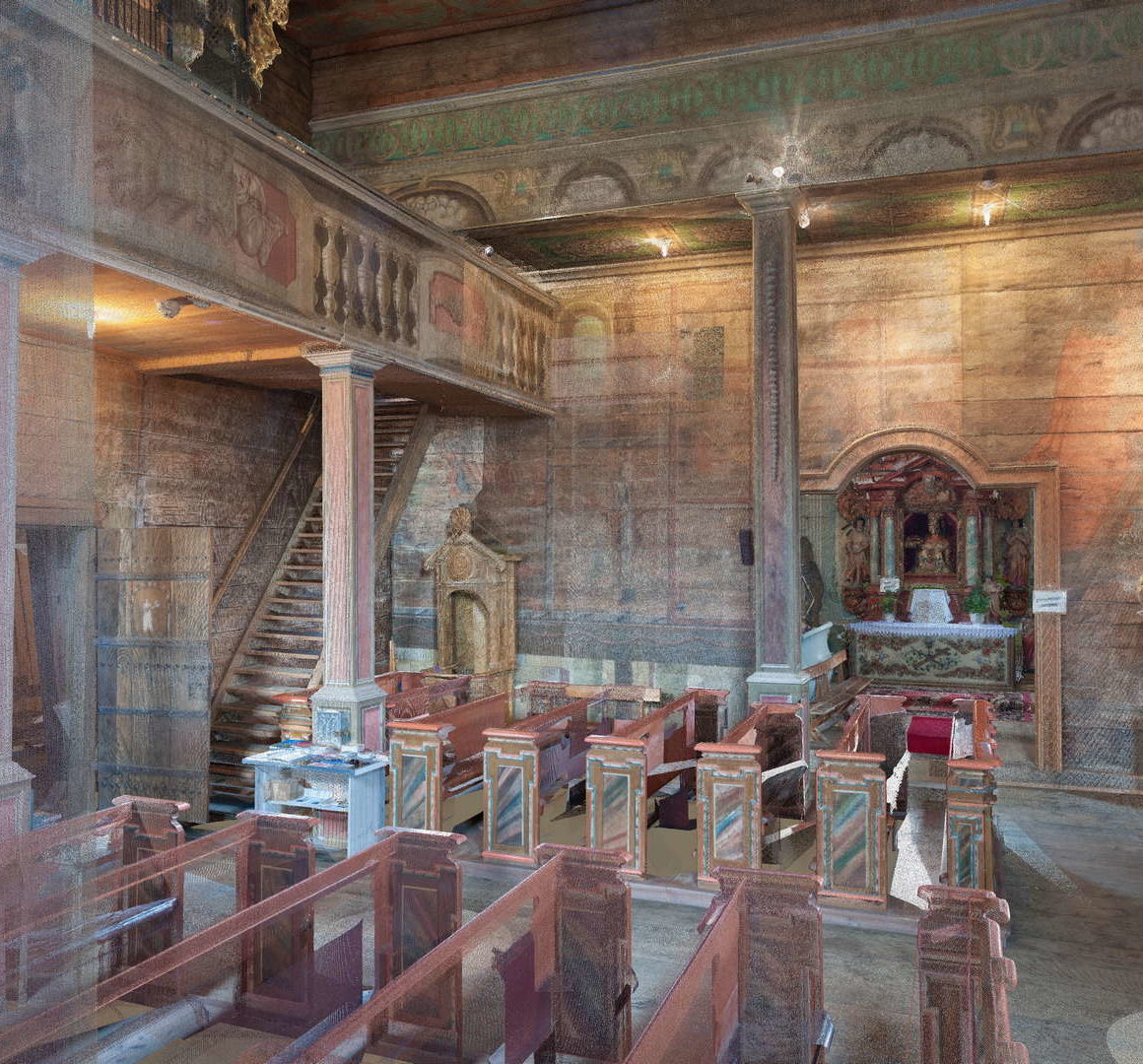

Haczów is currently home to the largest known set of wall paintings from the 15th century in Poland; it is the only set complete enough to allow us to imagine what the interiors of rural wooden churches looked like at the end of the Middle Ages. The murals represent the traditions of Gothic Kraków painting, but might have been made by artists from a workshop that operated in nearby Krosno. The total area of uncovered Gothic murals in Haczów is approx. 600 sq m. They tell a story from the beginning of the world and the original sin, through the history of redemption and the history of sainthood, to the announcement of the Last Judgement.

The 15th-century paintings were made on thin calcium and chalk ground, directly on a levelled wooden support. Figural depictions were arranged in two or three rows, and individual scenes were separated by painted frames. The trompe l’oeil depictions of architecture and painted fabrics were put in the plinth sections of the walls.

The northern wall of the chancel displays the Passion cycle; the uncovered plots include: Entry into Jerusalem, Last Supper, Washing of the Feet (?), Christ in Gethsemane, the Taking of Christ, Christ before Pilate, and the Carrying of the Cross. The eastern walls display the Crucifixion (destroyed by a window being moved), the Soldiers casting lots for Christ’s garments, and the remains of the scenes of Mourning and the Entombment of Christ. Most of the paintings on the southern wall of the chancel have not been uncovered, but we can assume they showed scenes relating to the Resurrection of Jesus. The only scenes visible today are those of the Coronation of the Virgin and the Martyrdom of St. Stanislaus as well as small vertical strips which reveal fragments depicting Archangel Michael, the Annunciation, and the Ten Thousand Martyrs of Mount Ararat.

The eastern wall of the chancel also displays images of saints. The lower area shows depictions of two female saints which are not very clear, and it was also where the foundation inscription could be found which, unfortunately, is now mostly illegible. On the sides of the central window in the middle wall, there are images of two holy bishops: Stanislaus (with his attribute, i.e. the figure of Piotrowin who was said to be resurrected by the bishop) and St. Vedast (Vedastus, Vaast) with a wolf holding a goose in its mouth.

The southern zaskrzynienie of the nave displays an Old Testament cycle; from the Creation of the World, through the Creation of Adam and Eve, the Original Sin, Exile from Paradise to the Work of the First Parents. Unfortunately, the murals are now in quite bad condition. The western wall of the nave was also decorated with scenes from the Old Testament: the Binding of Isaac, the Killing of Abel, and the Drunkenness of Noah (?), which are all placed above the matroneum. Below the matroneum and above the western church entrance, there is a depiction of the Veil of Veronica (the face of Jesus reflected on a piece of cloth belonging to St. Veronica). Another such image can be found above the southern entrance. The Veil of Veronica on the western wall shows Jesus with his eyes closed, which is a result of errors in reconstructing the fragment of the mural.

Below the zaskrzynienie, the southern wall of the nave was decorated with depictions of the female saints, now only partially preserved: St. Margaret with her attribute in the form of a dragon and St. Helen holding a cross are both visible today.

The western wall of the nave under the matroneum used to be decorated with a depiction of martyrs and the remains of the depicted scenes can be interpreted as the martyrdom of Saints Sebastian and Erasmus. The northern wall of the nave might have displayed the martyrdom of Saints Lawrence and Andrew; however, it is the immense image of St. Christopher that is the most-visible mural on this wall. We can also find here the remains of a depiction of St. Sophia and her three daughters.

The eastern (rood screen) wall holds the remains of the Apotheosis of St. Mary Magdalene. The remains of the boards of the original nave ceiling include the depictions of Salvator Mundi (Saviour of the World) and St. Michael the Archangel killing the dragon.

Fun fact: Sophia and her three daughters

Sophia is a legendary saint who is said to have been an early Christian martyr, the mother of three tortured daughters, called Faith, Hope, and Love. The story of the martyrs may be rooted in the allegorical concept of personifying the Three Theological Virtues as daughters of the Wisdom of God (Sophia). The cult of Sophia and her daughters might have developed at the turn of the 6th and 7th centuries. According to legend, persecutors of Christians decided to put Sophia through great suffering and told her to watch her daughters being killed one by one. The Middle Ages saw many different versions of the legend of St. Sophia.

One of them tells the story of a miracle when angels with crowns (sign of the martyrdom of the mother and the girls) appeared by Sophia and her daughters, with Sophia being entitled to seven crowns. Legend says she was tormented seven times, revived after each round, and finally killed, having received Holy Communion. However, you can also find a different interpretation of the seven crowns in the paintings of St. Sophia and her daughters: one crown of martyrdom is for each of the four saints, and the additional three crowns above Sophia’s head represent the three times the mother had to suffer watching the deaths of her three children.

Fun fact: St. Christopher the Giant.

St. Christopher is one of the most popular patrons, but he is a legendary saint: even his name is most likely to have been derived from legend. Christoforos means “Christ-bearer” and that is how St. Christopher was depicted: as a strong man carrying the Christ Child on his shoulders or on his back. Interestingly, legend says that the saint was supposed to be a giant (apparently he was about 7 metres tall). He was a very strong man and a great warrior who wanted to serve the most powerful master in the world. Once a hermit told him that Christ is the most powerful ruler, but if people want to serve him, they must devote themselves to helping others; then Christopher devoted himself to the work he was physically predisposed to, i.e. he settled near a dangerous river crossing and helped travellers to cross the river. Once, a little boy asked him to take him across the river; during the crossing,

Christopher suddenly felt the child was as heavy as lead, so much so that Christopher could barely carry him. When he finally reached the other side, he said to the boy: “I do not think the whole world could have been as heavy on my shoulders as you were”. The boy replied: “You had on your shoulders not only the whole world but Him who made it”. Of course, it was Jesus himself, and this way the giant became Christoforos, or “the Christ-bearer”. The gigantic depictions of St. Christopher used to be displayed in visible places, not only because the legendary Christopher was supposed to be a giant, but mainly because the images of St. Christopher were believed to have almost magical powers. According to medieval beliefs, they were to protect against sudden and unexpected death and everyone should, therefore, look at an image of St. Christopher to be safe.

Fun fact: the remains of St. Mary Magdalene in Ecstasy.

Mary Magdalene is a unique saint: according to the Gospel, a woman closely associated with Jesus and the first person to see the resurrected Christ. The most popular collection of hagiographies in the Middle Ages (13th-century “Golden Legend”) says that, after the Ascension of Jesus, Mary Magdalene decided to spend the rest of her life as a hermit. Living in isolation for 30 years, Magdalene would experience mystical ecstasy every day: seven times a day the angels would lift her up, and she would hear hymns of praise of the Heavenly Host, which served as a replacement for earthly food. It was during the time of her ecstasy, when she was being raised by angels, that Mary Magdalene was portrayed, especially in the late-medieval art of Central Europe.

The remaining fragments of the scene show us the angels, and the legs of Mary Magdalene, which are clearly covered with hair. Magdalene, raised by the angels, was actually depicted as being covered with hair almost all over her body, except her face, hands, and feet.

The late-Gothic images of Mary Magdalene might have been influenced by a motif from the legend of another saint, Mary of Egypt, who was venerated mainly in the Eastern Church. Mary of Egypt was believed to be a sinner who retired to the desert to live the rest of her life as a hermit in penitence, where her clothes crumbled to dust over the years, with her long hair being the only thing covering her nakedness. It is possible, however, that there is something more behind the “hairy” Mary Magdalene that we can find in medieval art: Mary Magdalene was not a perfect figure, but a sinner-saint. Her sinfulness was associated with her sexuality, since, according to legend, she was a former prostitute, and the concept of unbridled lust and sexual desire in medieval art was often portrayed in the form of the so-called Wild Men, covered with hair all over their bodies. In this context, the figure of a hirsute Mary Magdalene can be interestingly seen as a dualistic sinner-saint: she is a Wild Woman, because in the past she devoted herself to carnal urges, but now, after conversion, she experiences mystical ecstasy.